Introduction:

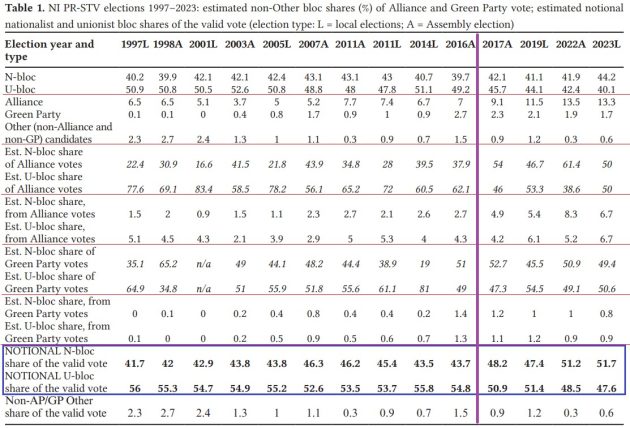

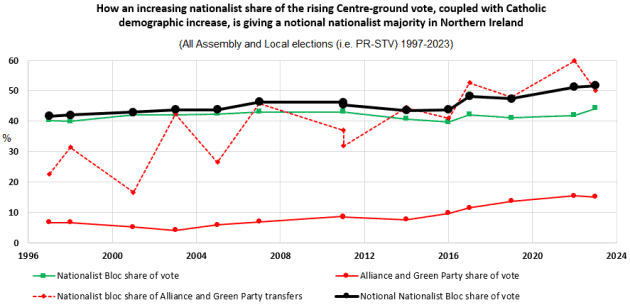

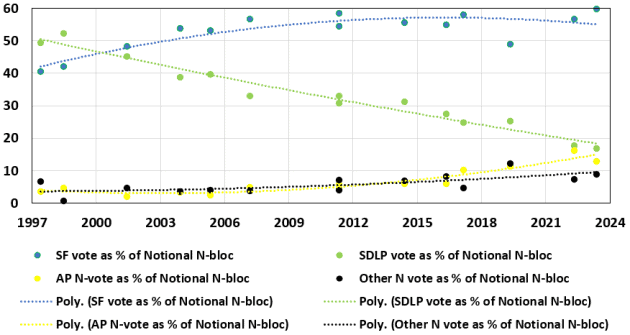

I recently published a paper in the ARINS section of the Royal Irish Academy journal Irish Studies in International Affairs (ISIA). My paper analysed transfers from Alliance and the Green Party for all Assembly elections (7) and local elections (also 7) between 1997 and 2023. The vote share of these two parties combined has increased from 4.1% in the 2003 Assembly election to 15.0% in the 2023 local elections. The nationalist bloc share has inched slightly upwards from 42.1% to 44.2% (and the unionist bloc has shrunk from 52.6% to 40.1%) in the same period. Why has unionism shrunk but nationalism not grown? What has happened, electorally speaking, to the demographically-increasing cultural Catholic vote since the BGFA? By looking at transfers from the two major Other bloc parties, I hoped to answer this.

I am not going to get into the methodology here: you can read the paper for details on this. But, in short, I calculated the N/(N+U) and U/(N+U) percentages every time an Alliance or Green Party candidate had either been excluded or had their surplus distributed. I then constructed a mathematical model that would allow me to infer what these two percentages would be for Alliance and Green Party candidates whose vote was neither excluded nor had their surplus distributed. I could then estimate the N:U overall ratio of Alliance and Green Party transfers (I will use AGP from now). If the nationalist share of AGP votes is added to the nationalist bloc share, we get the notional nationalist bloc (NNB) share. Similarly, the notional unionist bloc (NUB) can be calculated by adding the unionist share of AGP votes to the unionist bloc share.

Thanks to Professor Shelley Deane (editor of ISIA) for permission to re-use these images.

The data for NNB and NUB:

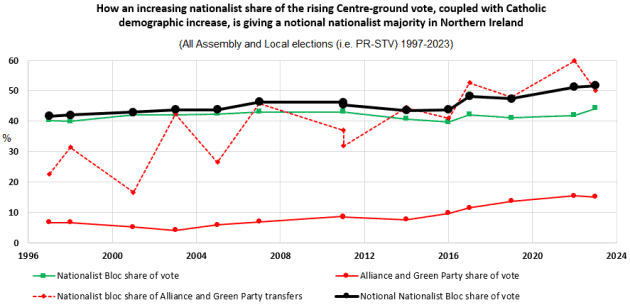

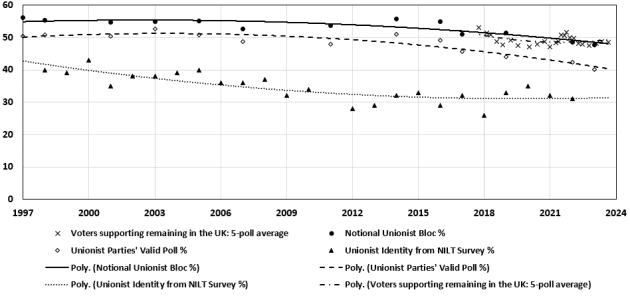

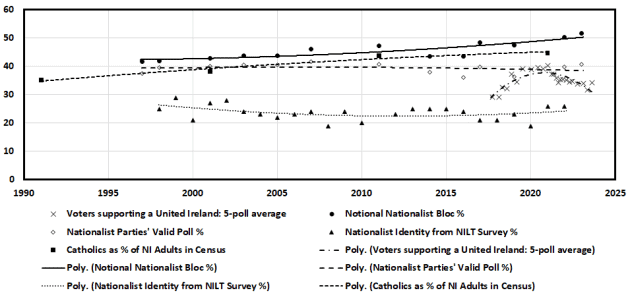

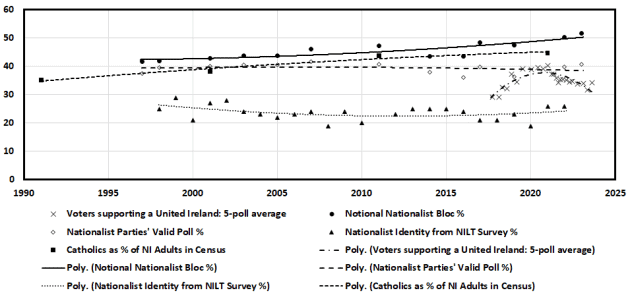

The figures in the table below (fig.1) show the notional unionist and nationalist bloc percentages were essentially flatlining until Brexit (the 2016 Assembly election occurred six weeks before the Brexit referendum; the purple vertical line marks the Brexit referendum). The graph immediately following (fig.2) shows the relevant data for nationalism. The big takeaway is that since about 2021 – one hundred years after Northern Ireland was founded – notional nationalism is the majority bloc.

Brexit: a psephological disaster for unionism:

After Brexit, unionism was hit with a triple whammy: its vote share dropped; an increasing Alliance vote transferred more to nationalist candidates; and the reduction of Assembly constituencies from six seats to five meant huge unionist MLA losses.

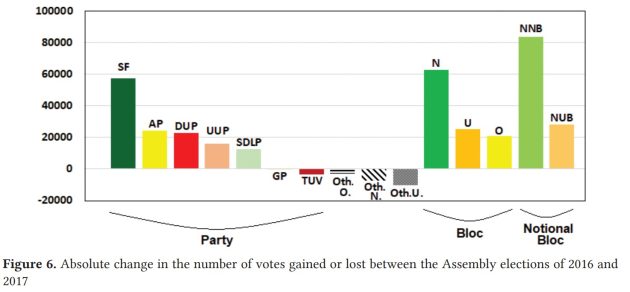

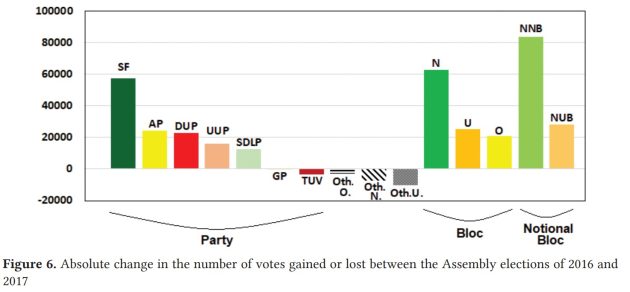

While the 2017 Assembly election saw a turnout increase of 10%, this was not uniformly distributed across all parties. Yes, the DUP and UUP both saw their absolute vote increase, but fig.3 shows that Sinn Féin in particular, and Alliance, were the big absolute vote gainers. Moreover, the nationalist share of transfers from an increased Alliance vote jumped from 38% to 54%. The overall effect of this was that the NNB gained almost three times as many votes between 2016 and 2017 than the NUB. Fig.2 shows that the Alliance vote is more likely to transfer mostly to nationalist candidates since Brexit.

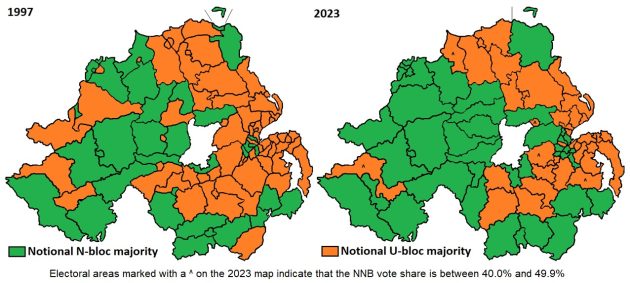

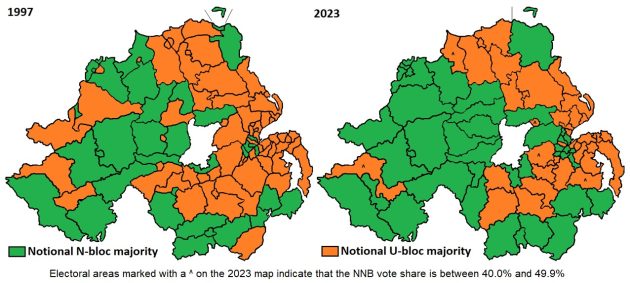

The geographic change in notional bloc dominance since 1997 is shown in fig.4:

Alliance: both a unionist and nationalist party?

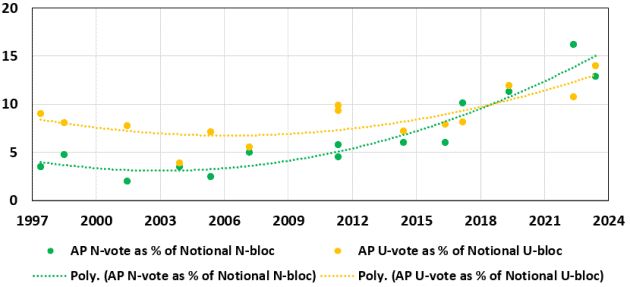

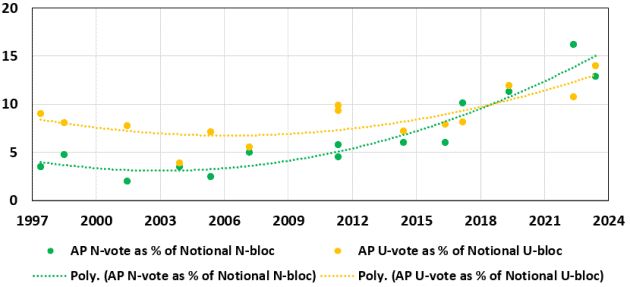

In the 2023 local elections, I estimate that Alliance transfers split evenly between unionist and nationalist candidates. Fig.5 shows that roughly one in seven notional nationalists (and the same ratio for notional unionists) give their first preference to Alliance but their lower preference reverts to one of the two communal blocs. Fig.1 (the sixth row with calculations) shows that pre-2007, only about one quarter of Alliance PR votes transferred to nationalist candidates; hence, the low green points on the left of fig.5. That percentage has now doubled.

Party share of the notional blocs:

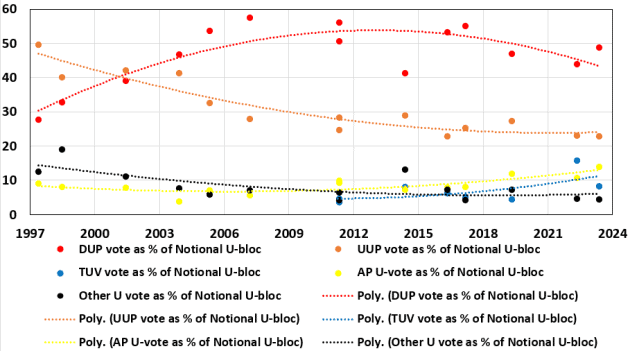

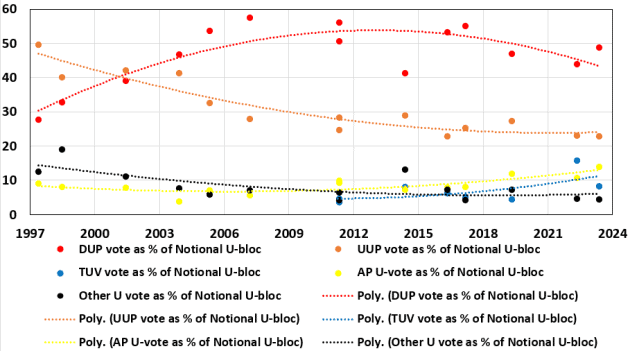

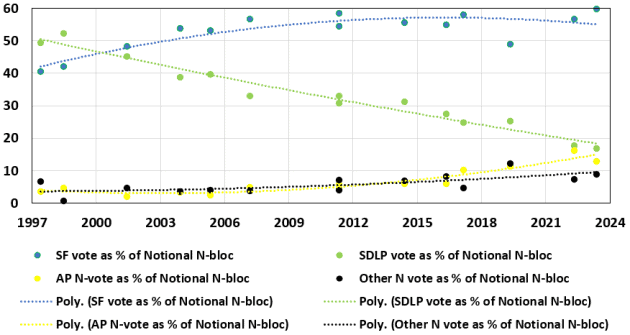

The following two graphs (figs. 6 and 7) show party share of the NUB (DUP, UUP, Alliance, TUV) and the NNB (Sinn Féin, SDLP, Alliance).

NUB:

The DUP’s share of the NUB has been on a downward curve since the Robinson era. The UUP has stabilized. Alliance and the TUV have both increased their share of the NUB.

NNB:

Sinn Féin have undisputed hegemony in the NNB. However, note the slight decrease in the best-fit curve since 2018. I am not saying that SF’s vote is declining, but it seems to be declining as a percentage of the increasing NNB vote share. (If Sinn Féin’s vote share increases by one percent, but the NNB vote share increases by five percent, then SF’s share of the NNB falls.) The SDLP’s share of the NNB has been doubly hit: by Sinn Féin up to 2011, and by Alliance since then. Alliance’s share of the NNB is now almost the same as the SDLP’s share.

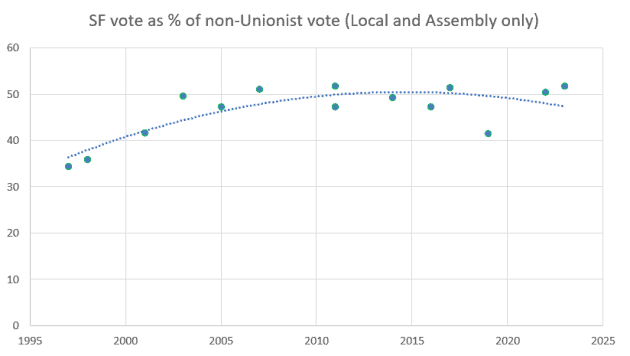

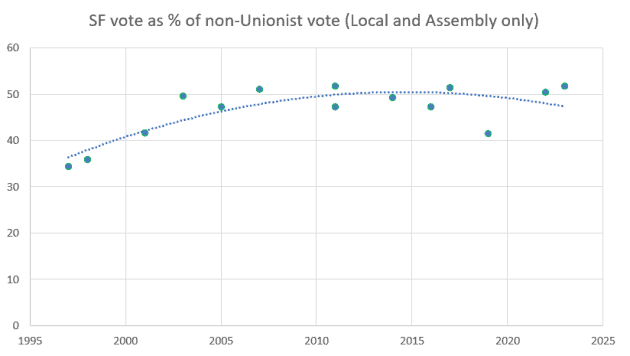

If we plot Sinn Féin’s share of the non-unionist vote (fig.8), we also see this recent relative decline:

If one looks just at the 2019-2023 datapoints, it looks as if Sinn Féin’s share is climbing significantly. However, it should be remembered that in 2019 Sinn Féin were boycotting the Assembly and Executive, and did less well at both local and Westminster elections. The 2019 point would likely have been higher had Sinn Féin been in the Executive.

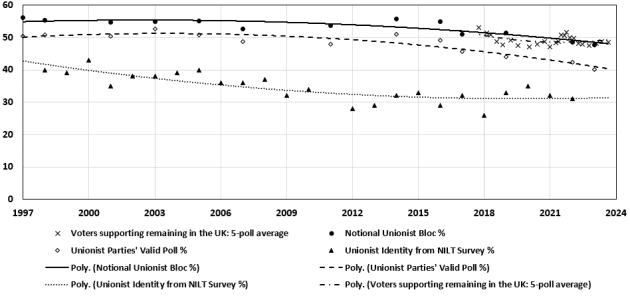

Unionism in trouble but the Union safe for the moment?

When we talk about unionism or nationalism, there are complex contexts. Do we mean how we vote, how we identify ourselves in the NILT surveys, or how we would vote on the Union/reunification question? Figs. 9 and 10 below show how the answers to these questions relate to each other.

The pro-Union share from surveys is always greater than the unionist bloc vote share (fig.9). By contrast, the pro-reunification share from surveys is always less than the nationalist bloc vote share (fig.10). Notice that the nationalist valid vote share is essentially horizontal, whereas the NNB estimated vote share is increasing, and essentially parallel to the best-fit line for Catholics as a percentage of the NI electorate 1991-2021. This indicates that an increasing percentage of Catholic voters are less interested in separatist politics and more interested in centre-ground politics.

Border-poll strategies for reunificationists and pro-Union advocates:

Both unionism and notional unionism are now a minority in Northern Ireland. Pro-Union campaigners will win a border poll if they both gain the support of unionist first-preference voters (and Alliance and the Green Party voters who transfer to unionist candidates) and some of the Alliance/Green Party voters who transfer to nationalist candidates.

The nationalist bloc was the plurality bloc in the 2023 local elections (probably due to relatively large turnout in west-of-the-Bann Electoral Areas {they ceded this epithet to the unionist bloc in this year’s Westminster election}). The NNB is the majority bloc now. Reunificationist campaigners will win a border poll if they can gain the support of nationalist first-preference voters (and Alliance and the Green Party voters who transfer to nationalist candidates). They don’t need any NUB voters. However, given the falling trajectory of support for reunification in surveys since 2021, they have their work cut out for them.

Philip McGuinness taught at Dundalk Institute of Technology, plays mandolin with the Oriel Traditional Orchestra and loves to walk around and over the wee perfect hills of the Ring Of Gullion.

Discover more from Slugger O’Toole

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.