[ad_1]

In 1979, Joan Didion published The White Album, a selection of essays that captured California on the brink of the 1970s, its counterculture dream beginning to curdle. “A demented and seductive vortical tension was building in the community,” as she described it. “The jitters were setting in. I recall a time when the dogs barked every night and the moon was always full.”

There is something of Didion’s description in Jessica Pratt’s fourth album, Here In The Pitch. The singer draws on the seedy history of her Los Angeles home, that peculiarly West Coast sense of an American utopia on the turn, to create her finest set of songs to date. Tales of sins and crimes and “evil innocence” lie beneath a musical palette of bossanova and orchestral ’60s pop. Melancholy moves below lustre. Sweetness buries the gloom. Even the album’s title suggests some latent malevolence. The ‘pitch’ in question refers both to absolute darkness and to bitumen; that oily black substance that forms, oozing and ominous, somewhere beneath the earth, and bubbles to the surface in places like LA’s La Brea Tar Pits.

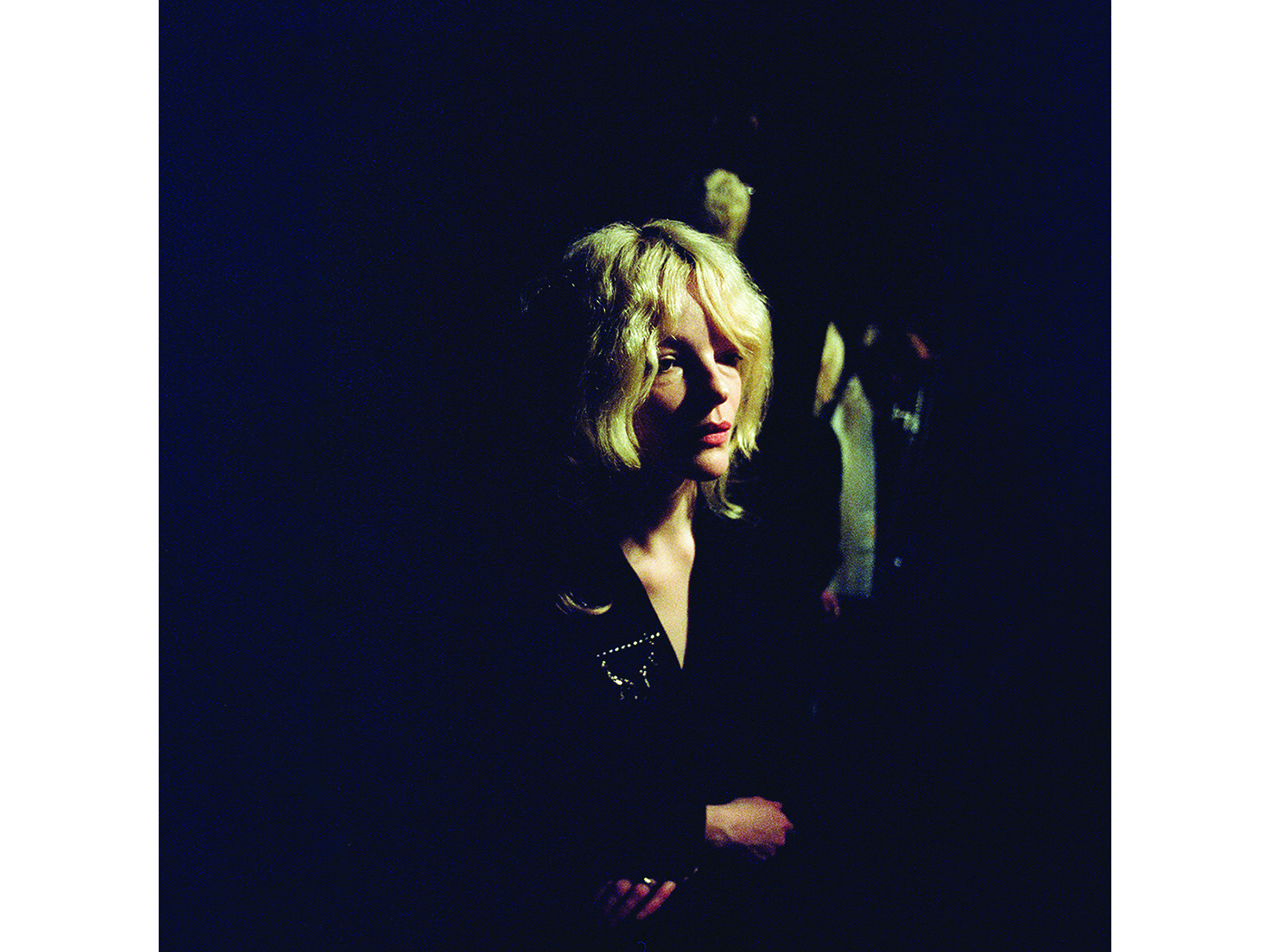

Since her self-titled 2012 debut, Pratt has established herself as a near-mystical figure. Her records are intimate and bewitching, but there is something half-glimpsed about her music, as if she and her songs are absorbed in their own intricate reverie. This is not a bad thing. Indeed it is a quality that only encourages audiences to lean in closer. Live shows inspire a kind of pin-drop reverence; as if one false move in the crowd might startle the singer from the clearing.

Pratt’s first two albums were recorded in rudimentary fashion – her debut featured analogue recordings set down in 2007, although they could reasonably have belonged to some earlier age. Tim Presley, who began a record label specifically to release the record, described it as “Stevie Nicks singing over David Crosby demos, with the intimacy of a Sibylle Baier.”

Its successor, 2015’s On Your Own Love Again, was no less primitive: a lo-fi, four-tracked and finger-picked affair made in her own apartment. Only in 2019, for her ‘breakthrough’ record, Quiet Signs, did Pratt relocate to a formal studio setting and work with a producer; her ambition to make something more cohesive and deliberate. Bigger, in a warm kind of fashion.

For Here In The Pitch, Pratt headed back to the same setting – Gary’s Electric Studios in Brooklyn, calling once again on multi-instrumentalist and engineer Al Carlson, and keyboardist Matt McDermott. This time, she also added Spencer Zahn on bass and percussionist Mauro Refosco (David Byrne, Atoms For Peace). Rather than overwhelm Pratt’s distinctive sound, these layers of instrumentation – flute and saxophone, glockenspiel and timpani, alongside her laminated vocals, work to swell the songs seemingly from the inside out. The effect is a cresting, rolling record of complexity and depth.

Pratt has spoken of how when she conceived of these songs she dreamed of “big panoramic sounds that make you think of the ocean and California”. Her touchstone, naturally, was Pet Sounds, but she sought that album’s moments of quiet as much as its baroque shimmer; the points at which you can hear the studio’s stillness; the feeling that “you could reach out and touch the texture of the sound in the air”.

The texture of sound is an intriguing thought in relation to Pratt. Her voice has always held its own extraordinary composition: sour, grained, sweet and reedy; as if in strange correspondence with the air around it. On early recordings, it bent towards Karen Dalton or Joanna Newsom, something high and lonesome. Here, her vocal runs lower and more weary – on “Empires Never Know” almost touching late Marianne Faithfull. This shift was a deliberate move; Pratt seeking a more physical mode of singing for this record. The result is a greater sense of range and a deeper kind of darkness.

Pet Sounds wasn’t the only inspiration for Here In The Pitch. Opening track “Life Is” strides in like a Phil Spector number, or The Walker Brothers’ “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore”. There are horns and strings and Mellotron, a guest guitar turn from Ryley Walker, as Pratt sings of insecurity and half-cornered frustration, chasing the circularity of her own thoughts as she notes how, “Time is time and time and time again.”

Oftentimes these tracks work this way, performing a kind of songwriting sleight of hand: the music moving brightly one way, while the lyrics draw in the opposite direction – small, tight, imagistic. On “Better Hate”, for instance, the music pitter-patters and sha-la-las, curlicued and sweet, but squint and you might see the honeyed vengeance of its lines: “Just a sad case, I’m nobody’s fool,” she sings, as if asking the way to San Jose. “And you’ve won it all, but your smile’ll be gone/When you’re yesterday’s news.”

Across these nine songs, the lyrics cast a world in which the light is low and the sun is dipping, autumn lies just round the corner. Its characters are trapped and untrusting. There are beggars and thieves, curfews and curses, lives “sunk in the middle” and “dreams of highways out”. Pratt’s songwriting may draw on dreamy ambiguity, but the themes on Here In The Pitch feel familiar; a kind of modernist Springsteen, pressed up against the Pacific.

This is a short album that was a long time coming, as all of Pratt’s records have been. But with each release the sense is never of a musician struggling for ideas, rather of an artist who is a master of distillation. “I was just trying to get the right feeling,” she has said of this record’s slow journey to release. It’s a testament to her talent that in the pursuit of that feeling, Pratt questioned so much of what had worked for her in the past, reconfiguring her sound, her band, her own much-loved voice. By Here In The Pitch’s close, she seems even to be having fresh thoughts about what led her here in the first place.

The album’s sole instrumental, “Glances”, arrives as a soft-lapping fingerpicked motif, surges with brass, then retreats. This wordless interlude cleanses the palate before album closer “The Last Year”, a track that proves unexpectedly hopeful, in a dark kind of way. “I think it’s gonna be fine, I think we’re gonna be together,” Pratt sings buoyantly. “And the storyline goes forever.”

With these two tracks, that ‘demented and seductive vortical tension’ gives way. The jitters abate and the dogs lie quiet, and even the moon begins to wane. We are out of the pitch, they seem to say, let us move toward the light.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

[ad_2]

Source link