Your support helps us to tell the story

As your White House correspondent, I ask the tough questions and seek the answers that matter.

Your support enables me to be in the room, pressing for transparency and accountability. Without your contributions, we wouldn’t have the resources to challenge those in power.

Your donation makes it possible for us to keep doing this important work, keeping you informed every step of the way to the November election

Andrew Feinberg

White House Correspondent

Humor can be an effective way to reach people who typically avoid information about colorectal cancer, a disease in which cells in the colon or rectum grow out of control.

A group of academic researchers across the country worked together to help develop what they hoped would be an effective messaging strategy to reach these people and — in the long term — encourage them to go for preventative screening.

The work comes two years after medical professionals advised that people start screening for the cancer at age 45. That’s something new, and may not be widely known. Before then, the recommended age was 50.

“We do all kinds of health messaging, research to see how we should frame messages. But, I wasn’t seeing anyone talking about how we should frame it for avoiders until Covid. And, I really saw an uptick of interest in information avoidance during Covid,” Dr Heather Orom, an associate professor at the University of Buffalo and the lead author of a study published last month in the British Journal of Health Psychology, told The Independent on Wednesday.

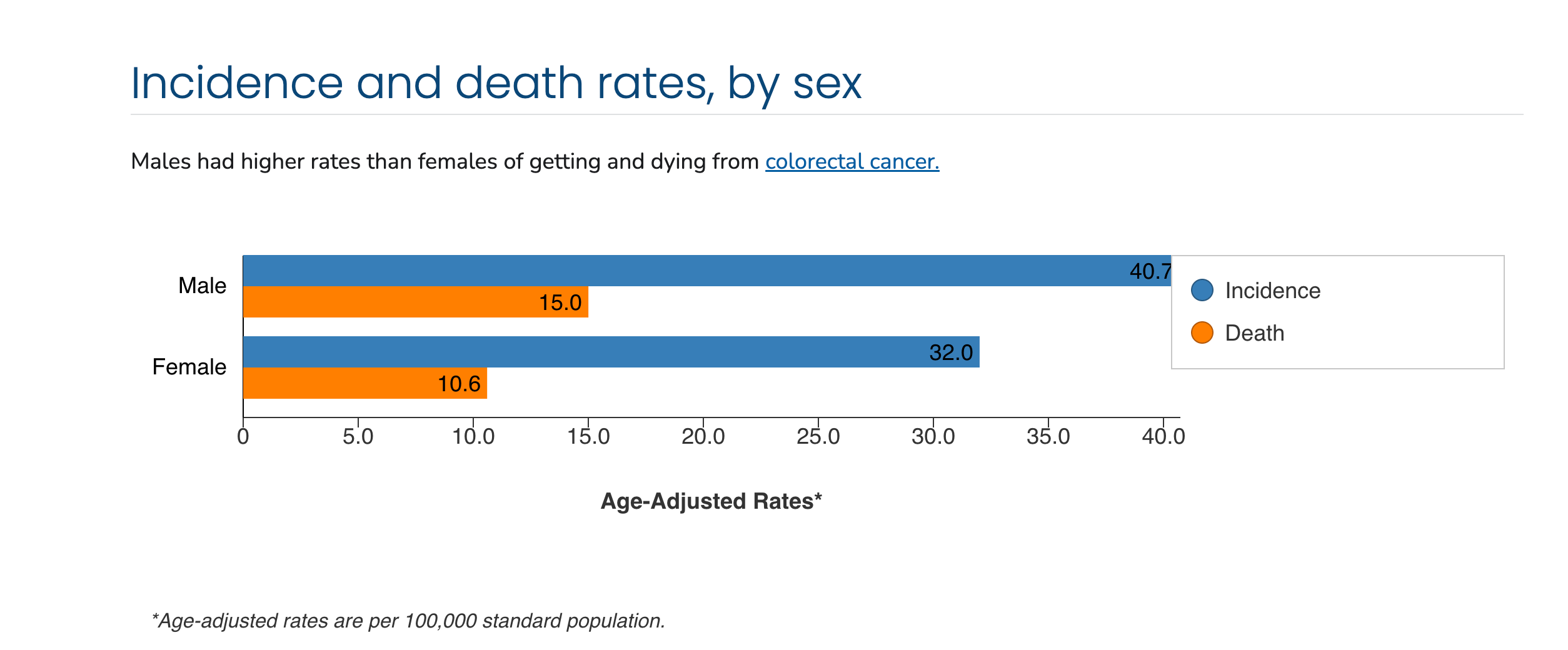

Routine screening for colorectal cancer is critical to reduce risk, and colorectal cancer is the world’s second-leading cause of cancer deaths. The risk of getting it increases as people age, but lifestyle and genetic factors can also raise risk. Affecting mostly men, it killed nearly 53,000 Americans in 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Symptoms of colorectal cancer, also commonly known as colon cancer, may include changes in bowel habits, blood in stool, diarrhea and constipation, abdominal pain or cramps, and weight loss with no explanation.

Previous research has found that around 20 percent of people may avoid information about colorectal cancer. Health information avoidance is a defensive behavior people deploy to stop negative thoughts related to having cancer or needing to make unwanted lifestyle changes. People can put off scheduling colonoscopies, avoid exposure to information, and delay obtaining information.

Those identified as avoidant are ranked on a self-reported scale, with their level of avoidance rated as “high” or “low.”

“The more avoidant you are, the more humor — it works for you to get you to engage with more information about colorectal cancer,” said Orom.

In two series of tests done last year, nearly 800 participants crowdsourced by the UK-based company Prolific took what they believed were online surveys, but were actually experiments. The tests were for people between the ages of between ages 45 and 75: the ages people should be screened for colorectal cancer.

After viewing a humorous comic, cute animal, streetscape photo, or coping message, participants were asked if they would like to receive a link to take a quiz and learn more about their personal risk for colorectal cancer.

The second test also asked people to choose between two videos: one about keeping feet healthy and another about colorectal cancer. The initial survey took less than five hours, and the researchers’ analysis lasted for just a couple of weeks.

In the tests, the study authors saw that comic strip cartoons — in one, a snowman picked his nose — made avoidant participants more likely to take the quiz. Similar exposure to humorous communication also made people more likely to choose to watch a short video about the disease. The cute animals and coping messages did not increase engagement.

The reason for this impact still remains unclear. Orom said in a statement that their original hypothesis was that the comics would put people in a positive mood, which would reduce the need to avoid threatening information. But, the findings could potentially improve public health messaging in the future.

Avoidance is a widespread issue, extending across medical fields.

“In talking with gastroenterologists or cancer surgeons, they also told me: ‘We see this all the time, that there are just folks who don’t want to think about it,” Orom said.

It’s a quality she says she sees in herself and her family when it comes to scary health topics.

“We all have people in our family who don’t want to think about threatening health topics, right? It’s really common.”