[ad_1]

BBC

BBCEngland has a housing crisis. Very few disagree. There are simply not enough safe, affordable, decent homes where people want to live.

Homelessness is at record levels with 150,000 children living in totally unsuitable temporary accommodation. Millions cannot afford to buy their first home.

The new Labour government believes the key is to build more houses. It has promised an extra 1.5 million in England across the five-year Parliament. But where will they all go?

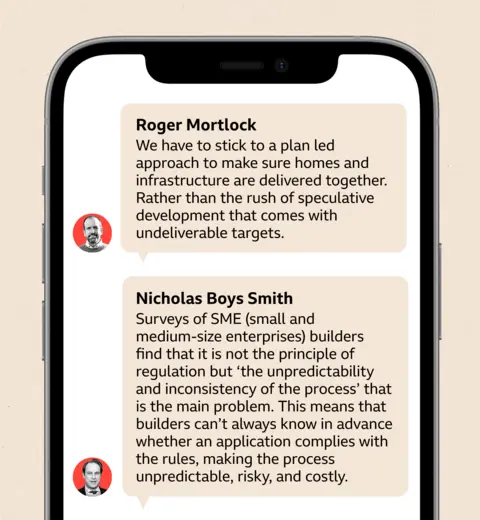

To discuss this question and the implications of housebuilding on a scale not seen for 50 years, I hosted a debate between three housing experts on WhatsApp to unpick what Britain should do about housing. What follows is an edited version of their conversation.

Meet the participants

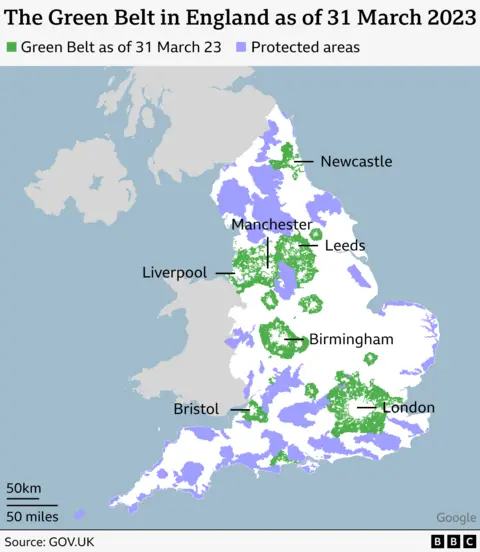

Should we build on the green belt or the grey belt?

Kate Henderson, you work for the trade body that represents providers of social housing. Let me start with you.

The government said it will build on brownfield sites first, land which has previously been developed.

But ministers talk of grey belt sites, bits of the protected green belt which are deemed to be unattractive.

Where should we build all these new homes?

We need a housing offer that works for everyone, building new homes and communities right across England.

It is right that we consider all options, including inner-city regeneration and building new communities, and we must ensure local people are involved in the process.

Thanks. The government, though, says it has a policy of brownfield first. In your estimation, is there enough brownfield land to build all the homes we need?

A brownfield first approach is great, but brownfield land alone won’t be enough to deliver the quantity of homes we need – not to mention, some brownfield land is not appropriate for development – so it’s right that the government looks at all options for meeting the housing need.

So, the idea that we can only use previously developed sites is flawed?

Roger Mortlock from CPRE, the countryside charity, what do you think?

People in this country are crying out for more genuinely affordable homes and homes for social rent. Building on the green belt creates very little of either.

We should build on the shovel-ready brownfield sites that – according to CPRE – have space for 1.2 million homes close to where people already live, work and go to school.

But I agree with Kate. Rural areas are also crying out for new, affordable homes.

Roger – Are there bits of the green belt that you would describe as grey belt?

I can see you want to come in here, Nicholas. I will come to you in just a moment.

The brownfield first commitment is great but it needs teeth.

Most of the green belt is high-value countryside that plays a vital role in tackling the climate and nature emergencies. Previously developed land in the green belt can already be built on.

OK. Nicholas – from Create Streets, a housing think tank – you wanted to come in here…

But do we need a bigger rethink of green belt land. It was designed to prevent sprawl but many commentators now think it is preventing vitally needed development.

Kate?

We know that not all green belt land is of high quality and the suggested classification of grey belt recognises that.

We also support the government’s proposals that where green belt land is put forward for housing, that a minimum of 50% of those homes should be affordable, with a preference for social rent.

What do to about Nimbys?

Roger – less than 9% of England is currently built on.

Isn’t it right that we take on the Nimbys (not in my back yard) and build the affordable homes our children and grandchildren so desperately need – even if that means upsetting existing communities?

The proposed definition of grey belt is far too woolly at the moment – and Nicholas is right, it could make lots of lawyers and landowners rich.

I think the whole Nimby/Yimby (yes in my backyard) polarisation is not that helpful and distracts from solving the problem of meeting the housing crisis head on.

The public have profoundly lost trust that creating new places or new buildings will improve their or their neighbours’ lives, as shown by multiple polls, by the politics of development and by pricing analysis of revealed preferences.

Even though 60% of the public support more homes, only 2% trust developers and only 7% trust planning to create new places. Until this improves, the politics of development will remain brutal.

We need to help people fall back in love with the future, thinking that new development can improve both places and their lives. Right now they don’t.

For the next part of the debate I have a graph showing house building in England since 1946…

If I may, Mark, one more point on Nimbys and land use, which is also relevant to the discussion on green belt.

By creating more places in which it is easy to get about by bike, foot or public transport as well as by car, and by retrofitting existing places to be like this, we can help create more homes on less land than by the infrastructure-heavy route we are currently taking.

On the same amount of land that was used for greenfield development last year, a report by Create Streets concluded that we could have built 220,471 homes rather than 112,240 if we had developed at an historic ‘gentle density’ of 55 homes per hectare instead of 28.

What’s the scale of Labour’s ambition?

Before we come onto the place-making bit, I wanted to reflect on the scale of Labour’s ambition.

We know that housing starts in the last financial year were less than 135,000. If the average to get to 1.5 million is 300,000 completions a year, we are already well behind what’s required. Years three, four and five may need closer to 400,000 a year.

I just wanted to get some thoughts on whether the 1.5 million target is feasible. We have heard such promises before, of course… Kate?

We did some research with Savills estate agency which shows, based on the current climate and private construction downturn, the only way the government can meet the 1.5 million homes target – equivalent to 300,000 a year – is by having a major investment programme in new affordable and social housing, alongside changes to planning.

Building social and affordable homes is great value for money for the government, according to research from Shelter and the National Housing Federation.

It helps bring down the benefits bill and save on homelessness prevention, temporary accommodation and the NHS.

One concern is that changes to the planning rules will mean that communities will have housing imposed on them, often without the infrastructure and services needed for all the extra people?

Roger?

We need to rethink how we deliver housing and get more diversity into the system.

There’s no incentive for the big developers to build more or faster. Large-volume builders dominate the market and often renege on affordable housing commitments.

Kate is right, we need investment.

Nicholas, you advised the last government on how to ensure new housing development creates places that make people proud.

What would your advice be to the new government?

Help local communities set really clear and unambiguous and locally popular local codes for ‘what development looks like round here’ and where it is to ‘de-risk’ development for self builders, all tenures and local builders in gentle density places.

Affordability and beauty. Can we do both?

Housing is a risky business. Many builders and developers have gone bust having built homes they couldn’t sell at a profit.

Viability is critically important – particularly with tougher rules on safety, sustainability and affordability.

Are we expecting too much with a pledge to build 1.5 million homes and to create beautiful new places?

The debate shouldn’t be housing quality vs housing quantity – we need both.

All homes should be well designed, meet the needs of residents and enhance their wellbeing – this means making sure they are accessible, adaptable, sustainable and crucially for us, affordable.

Quality is the path to quantity, resetting people’s expectations.

Is beauty an unaffordable luxury sometimes?

If we want local communities to accept new development, it’s really important that we plan in the infrastructure from the offset and understand the things that matter most to them.

For example, green spaces for children to play, local schools and local health services.

Is it a huge worry that we go for quantity rather than quality, make the same mistakes as in the past and create all kinds of social problems in communities which have no pride in the place they live?

No, because attractive places can be created at high density and lead to much higher property values (10-50%) which can pay for better infrastructure and more affordable homes.

We have to put quality first – for everyone.

It is surely madness that we can build zero-bill homes – homes that are cost-effective and zero-carbon – but they are not being used as a commonplace solution to the housing crisis.

Nicholas is right on density – we create more sustainable and less land-hungry developments if we think a bit differently.

As Nye Bevan said, “While we shall be judged for a year or two by the number of houses we build…we shall be judged in 10 years’ time by the type of houses we build” – I might add, that we will be judged in 100 years by the types of places.

It looks as though England is about to embark on a major housebuilding mission.

The answers to the where and the how questions will decide whether that policy solves problems – or just creates new problems for the future.

[ad_2]

Source link