[ad_1]

A thneed’s a-fine-something-that-all-people need.

-From The Lorax by Dr Seuss, 1971

Culture eats strategy for breakfast they say. I’ve long believed that Alex Salmond knew what a lot of his Scottish nationalist cohort never really did, ie that before movement was possible he would have to tackle the cultural barriers to his party’s appeal.

Irish nationalism in Northern Ireland has only fitfully understood that reality, in figures like Curry, Hume, Fitt, McGrady and Mallon and those all plied their trade at a time when it seemed plausible that NI Catholics might reach majority status.

So I start my fourth and last analysis on where we find ourselves after what much of the media called seismic change of the last election (the other three are on my archive page here) with a look at how slick marketing continues to triumph over reality.

It’s important to acknowledge that Sinn Féin emerged as largest party courtesy of the DUP vote fragmenting and splitting between three different unionist and post unionist parties. Further, it returned increased its majorities in the seats it held.

That problematic east west split, again…

Readers will be familiar by now with the east versus west/south split I’ve posited in all of my previous post election pieces. In brief, the east is drifting towards the highly competitive democratic norm of other European spaces (including the south).

The west and south however remains in something of a time-warp where the key political discourses remain stuck in the post partition motif of what an exasperated Churchill referenced in 1922…

The modes of thought of men, the whole outlook on affairs, the grouping of parties, all have encountered violent and tremendous change in the deluge of the world. The integrity of their quarrel is one of the few institutions that have been unaltered in the cataclysm which has swept the world.”

As the rest of Northern Ireland moves on into an era of democratic competition, the west and south (where Sinn Fein are dominant) remains stuck in a fantasy that unification will come if only Catholics can attain a majority. Yet it never comes.

In this belief they are aided by the fact this political line has been adopted by a large proportion of mainstream media figures as the approved narrative. It is accepted, even by English friends who take a close interest in the world, as inevitable.

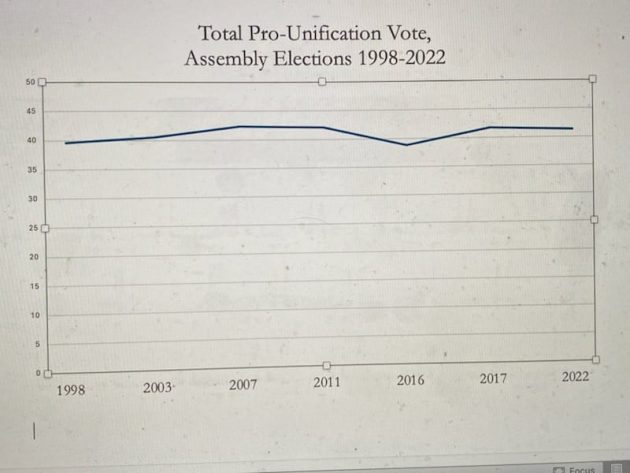

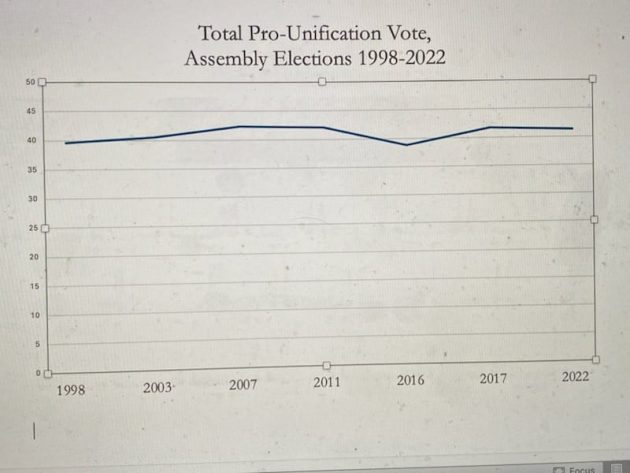

And yet, a look at the election results over the twenty four years that immediately followed the signing of the Belfast Agreement will show that in spite of Sinn Féin’s consolidation, the data clearly show there’s been ZERO progress towards unification:

If this rate of change were to remain stable then it is not unreasonable to suggest that there will never be unification. But of course we know that the pace and nature of demographic change cannot be predicted with any confidence.

Those expecting this change to happen of its own accord or the folly of their unionist opponents to deliver it for them via serial mistakes (Brexit was commonly cited as a milestone not just to unity but the end of the UK as a whole) are deluded.

If nationalists really do want political unity (and it’s not clear from the data that all do), they need to develop a different kind of political discourse, one that brings a form of tolerance into their own domestic political space that was not there before.

The problem with clever marketing

One of the things that gets said a lot is “a United Ireland must be close because look at how much we are talking about it?” But then you have to ask the follow up question which is are we really talking about it with any view to it being a practical reality?

For sure, we’re not talking about much else. But there is no indication (see the chart above) that it is having any real world effect. If Unionism is losing its appeal (and it is), there’s no evidence that a United Ireland is in play as an alternative.

Through the denudation of professionalised local journalism we now lack the means (or perhaps the curiosity) to probe memes like border polls or even Brexit (equally loved and despised journalists everywhere) that lead to stories that write themselves.

Our quotidian understanding of these matters relies on the casual passing on of controversial tropes rather than from any deeper understanding of what’s actually going on. The latest Oireachtas report on the matter offers an important insight here.

Of its 15 recommendations only the first two contain any element of substance, and these derive not from the work of the Committee On The Implementation Of The Good Friday Agreement, but Shared Island Unit research commissioned in 2022.

The rest of the recommendations read like motions from the People’s Front of Judea. With the exception of recommendations 1 and 2, which are entirely practical and sensible and not at all conditional on constitutional change, the report says nothing.

Recommendation 15 reads (and I kid you not) simply, The committee recommends preparation to begin immediately. As Newton Emerson noted in his Irish Times column last week, which conveys the Pythonesque nature of the piece…

The committee heard and received much expert testimony over more than a year, meaning a lot of firm views and specific ideas have been weighed up and boiled down to nothing.

Committee members would doubtless say it is not their role to decide the shape of a united Ireland. Still, could they not have taken a collective position on any of these arguments?

Newton ends by observing that if the report is saying nothing for worry of what unionists might think, they may give up. I doubt this is why the report is so thin. It’s more likely that the external marketing of a UI is just too far ahead of its support.

Republican mis-framing of the Irish problem

If the historically the English struggled to get to grips with the so-called Irish Problem, nationalism has one of its own, albeit one that’s barely evident in the south where below the five border counties few think in any sustained way about NI.

As we have seen in recent months Sinn Féin’s popularity in inner city Dublin has never relied on re-integrating the historic six counties of Northern Ireland but on loud oppositionalism to almost anything that moves within the coalition government.

It’s failure to retain its only European seat in Midlands/North West, never mind advance to two, demonstrates that it is losing ground to the anti immigration right and with traditional border republicans over the region’s lack of progress.

In the north, the party’s unremitting focus on retaining their monopoly of the Catholic dominant south and west of Northern Ireland has come at the price of them not being able to meaningfully compete in any of the discourses in the wider east.

This predilection for domestic political dominance ricochets into the nature of the story it (and wider nationalism) is able to tell around what it is to be Irish, creating a narrative weakness amongst those who feel themselves to be both Irish and British.

It also tempts them into easy but inaccurate tribal accounts of what’s happening within wider Northern Irish civil society (which at its most careless it lands it with responsibility for mega bonfires and loyalist flags in scattered single identity estates).

So it not only falls back into a tribal comfort zone, but its reflexive defensiveness about its own past attempts at getting a United Ireland (like the Provisional’s attempted military coup), has led it to be captured by the weaknesses of its own past actions.

Such accounts expunge ‘the other side’ from their version of the past. The row over a new Peacemaker’s Museum in Derry which purposely excludes any unionist participation in the bringing of peace, only further weakens their appeal to the “persuadables”.

For those who don’t know, a ‘museum’ has opened up in Derry called “Peacemakers”, consisting of a load of information about Sinn Féin people and a photo of John Hume, presumably to give it credence. Hume’s family have distanced themselves. Who funds it? Photos below.. https://t.co/pP2thC3vyh pic.twitter.com/748RWzkj7E

— Máiría Cahill (@cahillbooks) July 25, 2024

The Hume family made it clear before he died that if were he well “He would invite you to focus on a diversity of political views and political lives. To him, this level of just inclusion would be vital and non-negotiable.”

Rory O’Hanrahan charts the inclusion of a riot room for an immersive experience of Troubles era Bogside. War is peace, as someone once wrote. Even after huge public subsidy it costs a cool £18 (just £7 less than Titanic Belfast) to get in.

The stories therein may consolidate a minority opinion behind one party through further polarisation, but it also hinders the building of the broader coalition needed to create constitutional change. A step back to the past, rather than towards the future.

How Northern Ireland is different from the rest of the island

To chart the future you must look at Northern Ireland as it really is rather than pushing what you want to see. That needs a coming together of all experiences through social opportunities where people can bargain and trade in their social perspectives.

In fact, the Protestant experience of life in Northern Ireland (like the Irish Catholic experience in Scotland) goes back hundreds of years and is not only conditioned by historical experience (the rebellion of 1641 being a key one) but by geography.

We’re accustomed to seeing the island displayed in its projection on a north-south axis. It often excludes the other island (as the weather forecast on RTÉ used to do, but doesn’t any more) so that for many of us unity feels like the island’s natural state.

We can talk about an artificial border but all of them are manmade. Ask any Welsh speaker about the language heritage of west Herefordshire and the minor kingdom of Ergyng? Borders are also human artefacts that serve deeper social purposes.

So if the north-south axis is the normative view for most nationalists (and actually a lot of others), what happens if we tilt the map so that it displays roughly east-west?

The effect, the first time I saw it, was jarring as I angled my phone’s app towards home from the east on a beach near Portpatrick walking the dog before we boarded the ferry, .

Today travel to Dublin is easier from Belfast than Glasgow (as I’m sure any old firm supporter can affirm). In times when sea travel was easier than land, the two were almost as close.

From the history of North Down, we learn that Presbyterian congregations survived the Penal Laws by rowing for Portpatrick harbour from Donaghadee for services on Sundays.

Kelvin’s statue in Botanic Gardens is a reminder of Belfast’s close links to the energetic Scottish enlightenment, as indeed are the early Presbyterian leaders of the American Republic and even the earliest Irish Republicans in the late 1790s.

For well over a hundred years buses (and formerly trains) ran from Letterkenny to take local workers to (and from) the factories of Glasgow, the coalmines of Lanarkshire and seasonal prátaí-picking on the prosperous farms of lowland Scotland.

The old dialects of Donegal Irish and the Gaelic still spoken in the Scottish islands (that almost seem to hug the entirety of Ireland’s north coast) were interoperable in ways that the caighdeán oifigiúil in modern Irish schools no longer captures.

These are all cultural rather than political contexts needed to understand the Gordian knot that ties people in the north east (and north west) of the island to what is still the mainland within the jurisdictional union of Britain and Northern Ireland.

Yet many of these connections are denied or grudgingly reworked in ways that are easier to consume within nationalism’s tribalist heartlands, but make harder it for them to connect to those only weakly committed to any constitutional settlement.

The populist concept of time will erode belief in a United Ireland…

One of the great treasure houses of Belfast history is the Linen Hall Library. Its collection of books, journals, pamphlets and reports published in Northern Ireland is second to none. As is its collection of posters, especially from the early Troubles era.

One that stands out was a riff on an ecological campaign (Plant a Tree in ’73) holding out the promise of the Provisional movement: Ireland Free in ’73. It didn’t happen of course, like much else from that bloody time it proved far too provisional.

That moment has been repeated over and over ever since. From the promised Tet offensive of the late ’88 the failure of which led the Provisional movement to a path towards peace, to the giddy excitement in the run up to the disappointing 2001 census.

The ancient Greeks had two words for time. The one we’re more familiar in our modern everyday lives is chronos. This is time as defined by the calendar and the clock. It’s reassuringly quantitative and measurable, which is why SF uses it so much.

The primary attraction of using chronological time as a political rubric is that it is essentially predictive meaning that you are able to claim credit for things that haven’t happened yet. [Like Obama winning the Nobel Peace Prize – Ed]. Aye, maybe.

There are two problems with this approach. Once you bag the credit for your prediction, you are more likely not to spot opportunities that make your objectives more likely. And you allow others to falsify the claims as they fall void over time.

The other word is kairos. Not so much time as timeliness. In other words it’s a window of time during which actions can be most effective. For example the Shared Island Initiative researching educational outcomes without the burden of an endpoint.

The impossible task of describing an implausible outcome…

For much of the last ten years nationalist discourse has been consumed with the idea that if only it could describe what a United Ireland would look like it would be able to more effectively advance towards the ultimate preferred destination.

The poverty of ideas in the Oireachtas committee’s report, shows that Nationalism has not only no real ideas to share, it is also deeply ambivalent about how the southern state might welcome nearly 2 million new unreconciled residents into its tiny state.

The writers hints that they knows that any new state (whether unitary or federal) requires input from the broad swathe of both the Northern Irish and southern Irish citizens, but that it knows there’s no public appetite for indulging in blue sky thinking.

Partition is over a hundred years old and the divergence the report casually describes are huge departures in how each part of the island organises particularly in health and education services. Before 1922 many state school teachers trained in Dublin.

The report shows a marked reluctance to face the reality that while island life now has many convergences (there are over 200 organisations that operate on an island wide basis), the north east continues to maintain a much closer intimacy with Britain.

The oft repeated mantra that the Protestant middle classes are leaving for GB neglects two critical facts: many are doing bespoke courses aimed at NI students and will return after, and that more Catholics now study there than Protestants.

This is partly because being in the same jurisdiction it is easier to move to England to study than to Cork, Galway, Limerick or Dublin and partly because (certainly in the case of the last) it is just too expensive compared to Liverpool, Newcastle or Dundee.

Rather than describing a barely credible single solution to all our problems, the Shared Island Unit set out to identify pinch points in all island education to find mutual opportunities to make it easier to student/idea share, where it makes sense.

Waiting, Macawber-like, as most of northern nationalism has done over the last twenty odd years, for the wind to turn and switch to another direction certainly won’t fix it. Genuine change is hard, long term and at first at least, mostly thankless.

Yet there has to be a viable way forward for civic republicanism

I know some of you will be thinking this is all very bleak Mick, please, give us a break? If it reads that way it’s only because we keep driving up cul de sacs expecting to find a motorway to the freedom and change that most of us human beings crave.

But that’s a motorway still waiting to be built. In fact it’s less a motorway and more like living bridges we need to carry our hopes and dreams of a better fitting future. It won’t come from continuously stabbing each other in the back as we have been.

Yet to judge from the actions of successive NI Executives, you’d think that’s exactly what our politicians believe. What’s not obvious to outsiders (and I include political journalists and political scientists in this) is that 90% of politics is administration.

Whether it is organising an election campaign or running a committee or even a ministerial office, good administration and good governance are, in the longer term at least, a marker of real and sustained success. It’s most of what voters want too.

It’s important republicans see that this game is open to them too. Since most administrative barriers have been removed, what’s lacking is the confidence and belief that the keys to the future are in their hands now, not at some indeterminate point hence.

On the prospects of a united Ireland under a single administration of government back in 2008 Bertie Ahern laid out the clear reality of the situation that all republicans of good will must and should internalise:

“That can only happen in the long term future. How long that will be I don’t know. If it is done by any means of coercion, or divisiveness, or threats, it will never happen. We’ll stay at a very peaceful Ireland and I think time will be the healer providing people, in a dedicated way, work for the better good of everyone on the island.

If it doesn’t prove possible, then it stays the way it is under the Good Friday Agreement, and people will just have to be tolerant of that if it’s not possible to bring it any further.”

Two years later his successor as Taoiseach tuned up the same message even further:

“The genius of all of these agreements is that we are all on a common journey together where we have not decided on the destination. The problem with our ideologies in the past was that we had this idea about where we were going but we had no idea how anyone was going to come with us on the journey.

And then earlier in this summer Davy Adams warned his audience at Ireland’s Future:

Far from trying to convince unionists to support a new Ireland a sustained campaign of sneering and denigrating abuse have been directed at the via both social media and mainstream media. Unionists are constantly being told they are stupid, uneducated, disorganised, wrong headed and invariably sectarian.

He was applauded hugely by the audience for an act of courage, decency and generosity in telling them what they needed to know in order to make their project successful rather than telling them (as many already have) what they wanted to hear.

The Once-ler in Dr Seuss’s book sells a marketing dream of something “that-all-people-need”. Ultimately he destroys a whole community’s means of living up until they finally realise that his dream (not theirs) is not only empty but slowly killing them.

Co-operation is the glue that holds the key to a shared future…

But it is not all missteps. In spite of its soft launch (it is administration after all) the Shared Island Unit in the Taoiseach’s Office at the heart of Government Buildings in Dublin is the most important innovation in north-south cooperation in 100 years.

With the election of a new, post Brexit government in London keen to build bridges there’s an opportunity to get the institutions working at last but only if there’s a genuine partnership along the lines of that which delivered the Agreement.

But it requires both republicanism and unionism to become far more interested than they have been in helping the other fulfil their dreams by helping to build each other’s bridges, both real and metaphorical, to the south and west and, yes, to the east.

If we reach our goal, given what we have all gathered and agreed to do around the table, will it matter?

Will we mind? If others join, will they be welcome?

– John Kellden

Photo by Neslihan Gunaydin on Unsplash

Mick is founding editor of Slugger. He has written papers on the impacts of the Internet on politics and the wider media and is a regular guest and speaking events across Ireland, the UK and Europe. Twitter: @MickFealty

Discover more from Slugger O’Toole

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

[ad_2]

Source link