Colin Coulter is Professor of Sociology in Maynooth University. Here he asks some technical but searching questions about the gold standard ARINS survey, and why it is important to have a consistent base in such an influential survey.

While the criteria that might determine the calling of a border poll remain opaque, it is almost certain that opinion polls will have at least some bearing on the decision. The recent deliberations of a panel of experts, after all, concluded that surveys are likely to be among six data sources that might sway a Secretary of State into organising a ‘unification referendum’. That newfound significance has, of course, been both cause and symptom of the proliferation of opinion polls that has marked the post-Brexit era.

Among the spate of polls over the last eight years is a joint project between the ARINS network of academics and the Irish Times. That collaboration entails an annual survey based on face-to-face interviews with a large number of respondents and conducted by a reputable polling company. It clearly approximates, therefore, to the ‘gold standard’ for opinion polls set out by the aforementioned expert panel who pondered the mechanics of constitutional change.

The significance of the survey is heightened further, needless to say, by the blanket coverage it receives in a publication still seen in some quarters as the ‘national paper of record’. It seems likely, then, that the project will exert an influence over debates about Northern Ireland’s future that its authors, presumably, always intended.

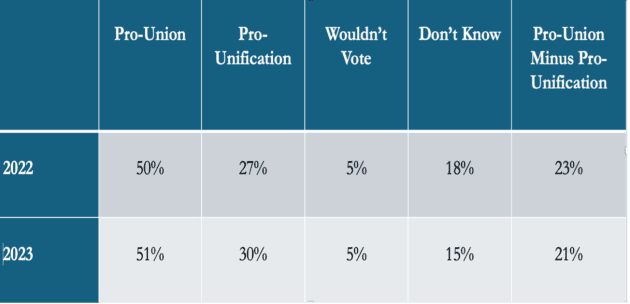

There have, to date, been two instalments of the ARINS survey. The resultant data that have been scrutinised most closely are, inevitably, those documenting the constitutional aspirations of the Northern Irish public. These headline figures from both existing editions of the survey are set out in the table below.

Table 1: Constitutional aspirations, ARINS survey, 2022 & 2023

What is most immediately striking here is that on both occasions support for the United Kingdom clearly outstripped support for a united Ireland. That finding is in line, of course, with the bulk of opinion polls conducted since the Brexit referendum. Some nationalist commentators were keen, however, to ignore the high levels of support for the status quo reiterated in the latest ARINS survey and search for the auguries of constitutional change instead.

First out of the blocks, predictably, was the journalist Brian Feeney. In his Irish News column, the prominent Ireland’s Future member offered the profoundly counter-intuitive assertion that ‘the headline figure which attracts most attention is the percentage in the north in favour of reunification: 30%, up from 27% last year’. Feeney went on to insist that the current level of support for a united Ireland disclosed in the survey is especially strong given that it exists ‘before the whistle’s blown for the start of the contest’ over constitutional change.

It’s hard to imagine a more wrong-headed characterisation of the state of public discourse in this part of the world. The starter’s pistol for the debate on Northern Ireland’s constitutional future was, in fact, sounded some time ago and it often feels that we will never get to talk about anything else. And the personal contribution that Brian Feeney has made to maintaining that miserable monotone has been on a scale that would have made Alexei Stakhanov blush.

The questionable interpretations that commentators place upon opinion polls are not, of course, the responsibility of those who generate the relevant data. There are, however, certain aspects of the ARINS/Irish Times project that invite misinterpretation of the current circumstances and future direction of Northern Irish political life. In particular, the survey heralded on the front page of Ireland’s most prestigious daily newspaper turns out to have some serious weight issues.

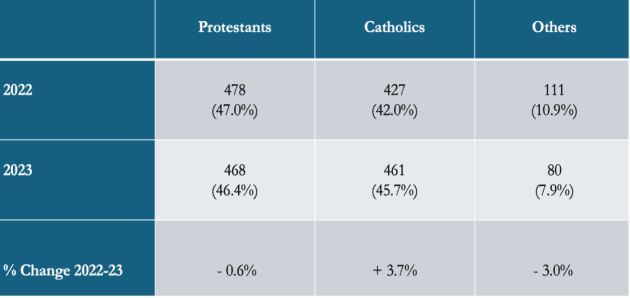

On closer examination, it becomes apparent that the existing editions of the ARINS survey are actually based on rather different cultural profiles of the Northern Irish public. The differences in the samples used in the two polls are summarised in the table below.

Table 2: Composition of respondents by ‘community background’, ARINS survey, 2022 & 2023

As readers will notice, there are some potentially significant changes here. Most obviously, the proportion of ‘cultural’ Protestants surveyed has fallen by 0.6% and the proportion of ‘cultural’ Catholics canvassed has increased by 3.7%. There has, then, been a 4.3% net change in the balance between Northern Ireland’s principal ethnonational traditions.

In addition, there has been a 3% drop in those sampled who belong to communities other than the pair that has traditionally dominated Northern Irish political life. That is a peculiar development at a time when those with no religious affiliation are clearly the fastest growing grouping in the region.

It becomes more peculiar still when we notice that the ‘other’ category here is in fact a composite in which atheists and agnostics share space with some strange bedfellows – those belonging to other religions, those who ‘don’t know’ their religious background and those who simply refused to answer. At a mere 5.4%, the specific weighting afforded to those with no religion in the 2023 ARINS survey is barely half of that in the most recent Census data, 9.3%. There is, therefore, a critical under-representation here of those who are unable or unwilling to recognise themselves in the familiar cultural binaries that continue to dominate and deform Northern Ireland.

It transpires that the weightings given to the communal blocs in the existing instalments of the ARINS survey differ so markedly because they are, in fact, based on two different instalments of the Northern Ireland Census. The 2022 edition of the poll was intended to reflect the composition of the population at the time of the 2011 Census, with the 2023 edition designed to mimic the composition of the population at the time of the 2021 Census. (Neither instalment of the survey models the respective batches of Census data with any great accuracy, as the matter of the ‘nones’ has already indicated, but we will leave that particular discrepancy for another occasion).

In other words, the first two iterations of the ARINS survey have, in fact, compressed ten years of demographic transition into the space of just twelve months. It is hardly surprising, then, that the data emerging from the project may have given the impression of change happening rather more rapidly than is likely to be the case.

Take what one prominent nationalist commentator deemed the ‘headline figure which attracts most attention’ in the most recent batch of ARINS data. Is the seemingly significant increase in the number of people aspiring to a united Ireland in that poll a ‘real’ shift in public opinion or merely a reflection of the change in the weighting of the people sampled?

If we were to increase the number of Catholics and reduce the number of Protestants in any survey we would, after all, expect a rise in the proportion of respondents opting for Irish reunification, even if nothing else has changed. So, how much of this potentially important shift is down to different sample weightings, and how much is down to people giving different answers to the same, timeworn questions?

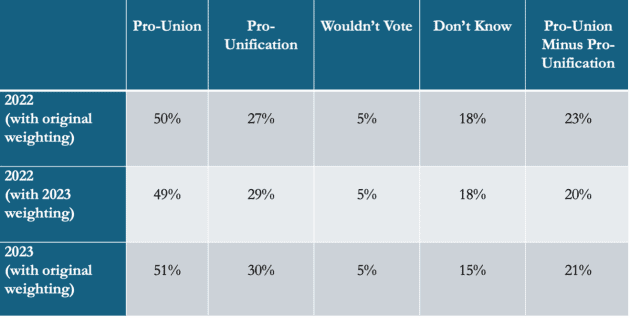

The most straightforward way of sifting out of the political from the methodological here is simply to use the same weightings for both instalments of the survey. Given that it is meant to model the most recent Census data, the sample of respondents in the 2023 ARINS poll is, clearly, the more appropriate basis for this particular exercise. In the table below, we can see not only what the original findings of both existing editions of the ARINS survey were, but also what the outcomes of the first instalment would have been had the weightings employed in the second instalment been used on that occasion as well.

Table 3: Constitutional aspirations, with original and altered weightings, ARINS survey, 2022 & 2023

This recalibration of the 2022 data brings about some fairly predictable results. With the 2023 weightings now applied, the level of support for the Union falls slightly (from 50% to 49%) and the level of support for a united Ireland increases slightly (from 27% to 29%). These different starting points mean that the degree of change between the two instalments of the survey are altered as well. With the weightings standardised across the two years, the proportion of people wishing to see the Union continue rises slightly more than before (up 2% rather than 1% previously), while the proportion of people wishing to see a united Ireland also rises but slightly less than before (up 1% rather than 3% previously).

That simple exercise suggests that the changes documented in the ARINS data are not merely methodological but political as well. Once we standardise the weightings across the two years, there remain, after all, some interesting changes in the political aspirations of the Northern Irish public. But those shifts are in the opposite direction to the one that the original ARINS data seemed to indicate.

As the table above illustrates, when we filter out the impact of the different sample weightings, we find that the second ARINS survey actually indicates a modest increase in support for the constitutional status quo not only in absolute terms but in relative terms as well. The final column intimates that while the data originally published in the Irish Times suggested a 2% net increase in support for Irish reunification, the actual underlying trend is a 1% net increase in support for maintaining the Union.

That is a rather different direction of travel to the one that had commentators like Brian Feeney so very animated. If, indeed, a phrase like ‘direction of travel’ even applies here. Such a modest degree of change is perhaps better seen as yet further evidence of the current condition of Northern Irish political life as an enduring, and corrosive, stalemate.

That only leaves us to ponder why it was that those who designed the ARINS survey chose to employ different sample weightings for polls conducted a mere twelve months apart. The explanation most likely to be advanced would be that it was just a matter of necessity. The field work for the initial version of the survey began, after all, in the late summer of 2022. And that meant that the cultural profile of the respondents had to be devised in advance of the most recent Census data being released in the autumn of that year.

A plausible explanation, certainly, but one that invites more questions than it answers.

The date on which the 2021 Census data were to be released fell just a month after interviews for the initial ARINS survey began and field work continued for several weeks afterwards. That schedule was known well in advance and it would, surely, have been possible to have delayed the project slightly to avail of the latest demographic detail on Northern Irish society.

Why the haste here? Would it not have made greater sense to have conducted the interviews a little later rather than base that first, crucial instalment of the survey on Census data that was already over a decade out of date?

And there is a further question that needs to be asked, one that touches on the crucial issues of academic rigour and transparency. Perhaps it simply wasn’t possible to delay the initial spell of field work. But if that were genuinely the case, was it not then beholden on those behind the ARINS survey to disclose the key alteration in the weightings that had occurred between the two editions when the data from the second instalment were released?

There is, however, no mention whatsoever of this critical methodological change. Across several weeks, the Irish Times devoted more than 25,000 words to the second instalment of the ARINS survey. Amid all that coverage, there is not a single mention of the fact that the cultural profile of respondents in that edition had changed appreciably from the one in its predecessor.

That, clearly, is a rather glaring omission, and may well be indicative of deeper problems in a project which aspires to play a critical role in debates about (Northern) Ireland’s future. It would appear that at least some at the helm of the ARINS enterprise may well be aware of these shortcomings.

That might explain why their survey data disappeared from the internet over the summer and why some have yet to resurface. It remains to be seen whether the recent changes behind the scenes in the grouping will prove sufficient to resolve the existing problems in its capstone project before the third instalment appears later this year.

There is, finally, the familiar question of why we should take any of this under our notice. The most obvious answer is that the issues raised here matter precisely because the ARINS survey has the potential to matter a great deal. As mentioned at the outset, such ‘gold standard’ research will continue to exercise considerable influence over the seemingly endless debates about (Northern) Ireland’s future and may even have some bearing on whether a future Secretary State decides to call a border poll. In light of that significance, it is especially critical that the ARINS survey is constructed, and indeed reported, in a manner that is robust and transparent. That is the very least we should expect.

This is a guest slot to give a platform for new writers either as a one off, or a prelude to becoming part of the regular Slugger team.

Discover more from Slugger O’Toole

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.